- Home

- Stella Russell

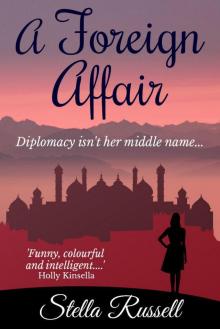

A Foreign Affair Page 5

A Foreign Affair Read online

Page 5

My heart pounding, feeling the blood freeze in my veins, I hung my head as low as I could while they set about sealing my fate, in a more or less disorderly democratic fashion. It was a dead heat, three against three but a moment later they seemed to have lost all interest in the project, lolling back on their cushions for another round of qat and more cigarettes, and some more exaltedly overexcited chatter. I told myself that for as long as no one made any move to fetch either of those dreaded small electrical goods, I was not going to abandon all hope.

And then the atmosphere changed again. Jacuzzi fanciers Abdul Wahhab and Abdul Rahman fell out over a cigarette, the last in the latter’s pack, the one he’d been carefully saving until Abdul Wahhab had selfishly helped himself to it. The resulting skirmish looked about to turn fratricidal until the Brummie intervened to arbitrate, and what I feared most was the upshot of that: Abdul Wahhab declared he’d rather throw in his lot with the trio of my wannabe executioners than even consider going into the hotel business with Abdul Rahman. ‘No need for another vote,’ said the Brummie, gleefully rubbing his hands together while a thin stream of green qat slime that had burst the banks of his lips slid down his chin, ‘it’s four to one in favour now…’

‘But what about me?’ I interjected desperately, clutching at a qat stalk of a last straw, ‘I have the vote too in this democracy, don’t I? With my vote it’s three to four, and shouldn’t I get two votes?’

‘No? Why?’

‘Because – because I come from a country that’s allied to a country that could send an unmanned drone aeroplane to track you down and blow you to smithereens wherever you are, in bed, at a qat stall, if you decide to go ahead and chop my head off…’

‘So extra-judicial assassination’s another kind of democracy, is it? Letting some moron in Nevada with a joystick in one hand and a hotdog in the other play God is humanly righteous, is it? Is that the rule of law the West is always crapping on about?’ the Brummie shot back, more furiously angry than ever.

Ceding the point to him helplessly, I changed tack: ‘- but another thing: I’m a very attractive woman and almost old enough to be your mother, so I deserve your respect,’ I blurted, ‘Your Koran says something about honouring your elders and respecting women, doesn’t it?’

How was I to know what their Koran said? I was just banking on them having no more idea than I did, but I couldn’t keep the note of hopelessness out of my voice now that the instruments of my destruction had begun to appear, along with some neatly laminated Koranic inscriptions which Abdul Wahhab, the keenest of recent converts to Islamist infamy, was busily tacking to one of the breeze-block walls of the car port. Saeed was unknotting the flex of his shiny carving knife while Haroun bossily commanded the studio set, deciding on a Moslem green back-cloth and positioning a pile of cushions he covered with another length of the same blue and white striped plastic sheeting that had served as a tablecloth at lunchtime. My stomach heaved. The contents of my bowels threatened to liquidise at such incontrovertible proofs that sensibly hygienic preparations were being made for relieving me of my head.

I never dreamed that I’d find myself saying anything of the kind but, ‘Please, just put me up against a wall and shoot me,’ erupted unbidden from the core of my being, ‘What’s the point of all this putrescent palaver?’ The words that come to mind when one is under duress!

‘Durrr! Because we want the clip to go viral on Youtube, don’t we?’ said the Brummie, grabbing me firmly by the arm, forcing me to adopt a kneeling position on the plastic sheet, indicating that I should bend to place my head, my neck exposed, on the upturned wooden ammunition box he’d put there. ‘It won’t take long with this new knife, it’s a Bosch…’ he added in a soothing tone, as my bowels prepared to make good their threat of a last heroic assault on my murderers’ nostrils.

The inscriptions and I were in place, the camera rolling, the knife plugged in and whirring, eager to go about its grisly business when the Brummie’s mobile rang. Suddenly, gone was all his swagger and braggadocio. Suddenly, I could tell by his tone it was yes, no, three bags full to someone on the other end and the name al-Majid was being bandied about among the brothers in hushed, reverent tones, again and again, which is why it stuck in my memory, and thank God it did, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

In an instant, the show was off, cancelled. The inscriptions were torn down, the executioner’s platform and block dismantled, and the camera and knife hurriedly concealed under a pile of cushions, as if inspection by a feared headmaster was expected. The shock of my reprieve was so great that I was tongue-tied, rooted to a spot in the qat-stalk strewn centre of that carport, waiting for my erstwhile torturers to decide what to do with me next.

Chapter Six

My first day in Yemen had still other surprises in store for me but nice ones, for the most part.

For a start, the shrivelled and toothless old mummy, greedy but apparently capable of neither speech nor thought, whom I’d noticed at lunch turned out an ally, but I wasn’t to know that immediately. I’ll have to rewind a little.

Shepherding me back towards the comparative safety of the mud castle, my would-be executioners permitted me a detour to the LandCruiser to fetch my suitcase. Just like those guards of the Anglican church compound, they were enchanted by the case’s shiny rounded contours, its sliding retractable handle and neat little wheels. I rather gathered that the gift of my precious treasure chest to them might have a bearing on my final fate in that place, but resolved not to think of surrendering it unless absolutely sure that, in so doing, I’d be saving my life. Trundling my treasure chest on, through the pebbles and dust towards the castle entrance, I found myself fantasising about embarking on a country hotel weekend and requesting a private room with an en suite and perhaps some boiling water in which to dunk an Earl Grey tea-bag.

In the gloomy castle interior the television had been re-tuned to al-Jazeerah; bin Laden had released another of his edicts. I glimpsed the usual ropey old footage of him clambering about in his sandals on some rocky hillside which, it struck me, could easily have been somewhere not a million miles away, right there in south Yemen. No one but me was paying him any attention. Instead of a tangle of tumbling children of all ages and sizes, only that ancient wizened mummy was squatting cross-legged against one of the walls in his grubby-looking futa, eyes shut, puffing at a home-made shisha. The unfamiliar trundling rumble of my wheelie-case was what roused him and, in an astonishingly strong voice, he shouted in English: ‘What in the name of the God and his Prophet – peace be upon him! - have you got in there, my dear?’

I was too taken aback by both the nature and volume of the sound issuing from that bag of bones, and by my flash of insight that I might be face to face with a real power of the establishment at last, to venture anything but ‘Roza Flashman, how do you do?’ and extending my hand towards him to shake.

‘Flashman? Did you say Flashman?’

‘Great great granddaughter of Sir Harry,’ I confirmed.

‘Ahlan wa sahlan! Welcome! Any fruit of those lustrous loins is as welcome in my home as the Prophet himself would be!’

Thank God for my illustrious, lustrous-loined ancestor! However it had come about that this living fossil of a Yemeni knew both excellent English and all about my great great great grandpa, I gave instant and happy thanks by furtively kissing the icon of Russia’s St Serafim of Sarov which I always wear around my neck.

‘My dear, I fear I must apologise for my sons’ boorishness. Of course, I have done my best to inculcate both manners and moral fibre in them but the results have been patchy, at best. Most regrettably, force of circumstance meant that I was never able to pack them off to my alma mater and Flashman’s, Rugby, for the cold baths and cross country runs regime I was fortunate enough to enjoy in the 1950s thanks to your esteemed Colonial Office. I see you are confused. My dear, I was one of those who benefitted by a most enlightened programme of boarding school education for the sons of sheikhs in the

good old days. A good English education – the best in the world – was what did the trick for me!’ He sighed and puffed on his shisha. ‘But it has to be an English public school like Rugby. I made the mistake last year of sending my Salih to a Birmingham business college which has done him no favours at all; he left a good-natured dreamer and returned six month later, a bad-tempered brute with the filthiest accent I’ve ever heard!’ he complained, emitting a cloud of rotten apple-scented smoke. ‘I do hope you’ll be able to find it in your kind British heart to - how shall I put it? - forgive them any trespasses against you. You know, my dear, I loved going to school chapel and saying that prayer every morning ‘Our Father, who art in heaven….How does it go on?’

He didn’t need much prompting and, while his six sons looked on – presumably appalled to the cores of their Moslem or, in at least two cases, fundamentalist beings - we recited the whole thing together, shouting out our final Amen! Then, waving his boys away with a flick of his wrist, just as if they were a handful of bothersome flies, he motioned me to settle down on the mattress beside him and zapped the volume on the TV.

‘You know, Abu Abdul Wahhab, ’ I began confidingly, seeking to enhance our new intimacy by addressing him according to the Arab custom as the father of his eldest son. ‘I understand your disappointment – your Salih is a brute and you may be interested to know that Saeed was about to behead me with an electric carving knife, but when you’ve got six sons you can afford a few bad apples. There are two with a bit of entrepreneurial get up and go about them, I would say, and Hamza strikes me as a very sensible lad…’ I was hoping to build on my Flashman advantage by expertly steering the conversation around to how I must, without further delay or hindrance, be transported to the Aden Sheraton.

On a different wavelength altogether however, the old man answered: ‘You think I have only six sons, my dear? But you have met at least twelve of them since you arrived – to tell you the truth, I forget how many I have now, it could be twenty-two or twenty-four – twins were born last week – I forget their names…’

The same prurient nosiness that can rivet me to the pages of Hello magazine at the hairdresser’s now prevailed over any anxiety I was still feeling about my abduction. I would have given quite a lot – my Laura Mercier mineral powder, say - to know more about the life and loves of this old Yemeni stick insect who’d already seized my left hand and begun using my fingertips to count off the names of his male progeny: Abdul Wahhab, Abdul Rahman, Saeed, Haroun, Hamza, Salih, Mustafa, Hamid, Walid, Abdullah…What a subtly erotic game that was! And he knew it.

‘Now behave yourself!’ I told him firmly, ‘I’ve had more than enough shocks for one day and you’re old enough to be my grandfather!’

‘Grandfather? You flatter me! I’ll have you know, my dear, I’m already a great-great-grandfather,’ he said, cheerfully re-adjusting his futa, ‘and so what, when my youngest wife is three years younger than my eldest son’s youngest daughter? Fatima is only seventeen. I’m old enough to be her great-grandfather!’

‘Fatima is your wife?’

‘Of course! How else do you think she can dress and act the way she does? All my daughters, my daughters-in-law and my granddaughters are much more fashionably conservative in their outlook and dress – they all go for that black bat-out-of-hell look.’

‘Don’t their men insist on it?’

‘Usually it’s the women who believe they look more up to date and elegant draped in a black sheet like that, but sometimes, yes, it’s the men. Saeed and Haroun fret that every man they meet is longing to bed their wives but they also believe that pretending to live in the time of the Prophet – peace be upon him! – will buy them front row seats in Heaven - Pah! (Another emission of nauseatingly sweet smoke) Whoever heard such nonsense? Do they do without a car or a mobile phone? And I ask you, what kind of technology must that infernal Jesus lookalike-‘

‘Who?’

‘Their hero, Osama Bin Laden of course! How much technology must he have stashed in his hide-out to be able to broadcast his nightmares to the whole world? Curses be upon him for his disaster movie fantasies!’ (Puff…bubble!) ‘If I were him, I’d have a good medical check-up! Perhaps he doesn’t know that old Latin tag – ‘mens sana in corpore sano’- that the physical and the mental are as intimately connected as a man and woman having intercourse? (Puff, puff!…he straightened his futa again) My dear, I solemnly swear to you that none of these violent catastrophes need have happened at all if Britain hadn’t handed Palestine to the Jews in 1917 and if all our young men had been raised on regular rugger matches and doses of rosehip syrup and cod-liver oil, with stewed prunes for their constipation of course. God is great but do you think I could have impregnated the eight wives I’ve had with an average of eight children apiece without the benefit of all those excellent things, plus Chilprufe vests, and Vic’s Vapour Rub?….’

I had to tune out, suddenly exhausted by this riotous rag-bag of insights into the causes of Islamist terrorism. One thing was abundantly clear to me: the political complexion of that household was richly varied, and this powerful patriarch and his youngest wife might well be the most modern and progressive members of it, at least from a western point of view. I couldn’t be a hundred per cent sure that his political sympathies lay with the south Yemen nationalist Hamza, but it seemed likely given his British public school upbringing and fondness for my forebear. On the whole, I decided, I was probably as safe as I could be and began to yearn for a stiff drink.

‘You wouldn’t happen to have a drop of the hard stuff lying around, would you Abu Abdul Wahhab?’ I said, carefully selecting a mode of speech he would certainly have been exposed to in 1950s Britain. As I spoke, I glanced around me as if expecting to spot a well-stocked cabinet or heavy-laden drinks trolley.

‘Ah! If only!’ he replied, cross at having his reverie ruined, ‘What I wouldn’t do for a cold beer or a vodka on the rocks! We drank like fish while the British were here and like whales as soon as the Communists took over – the Russians introduced us to their vodka and the East Germans came and built a brewery – but that’s all changed since unification with the north. Here and there one can come by cans of beer or bottles of perfectly frightful Djibouti whisky, but they cost the earth. Do you know, my dear, other people complain that the northerners have stolen our land and taken our jobs and flouted all our laws but personally speaking, the alcohol ban is what I find the greatest inconvenience about being ruled from Sanaa. It’s enough to make any sane fellow rush to join this new movement for southern Yemeni independence…’

So disappointed by his negative answer was I that I barely registered this confirming sign of sympathy with Hamza’s politics. I was far too busy trying to recall whether I’d had the good sense to slip that bottle of cooking sherry into my case; I recalled that I’d hesitated because of its size. There was nothing for it. I’d have to open up my treasure chest after all. Scrambling to my knees I lurched towards it and fiddled the numbers of the combination lock into their correct sequence: 040487, the date of Ralph and Fiona’s wedding, the day I was robbed of a brother and saddled with an adder. Yes, there it was, nestling safely between a bath-towel and a hand towel, near the top.

Meanwhile, the old boy’s hawk eye had alighted on the can of baked beans: ‘My favourite!’ he roared, ‘even the Prophet – peace be upon him - in all his seven heavens has never tasted such a food as this! My dear, I confess to you that I wept when I left England – not for my school-friends or the beauty of your green and pleasant land but because I could only fit five cans of Heinz beans in my trunk!’ He had overturned his shisha and was weeping with joy now, one skinny twig of an arm already extending itself to grab that unlikely treasure from its snug towelling cradle, when a lightning thought occurred to me.

‘Not so fast, Abu Abdul Wahhab! Not so fast!’ My arsenal was going to start earning its keep.

‘I only want to look – to hold a can of baked beans in my hands again, just once before I die!

’ he begged, tears coursing down his dried fig of a face.

‘And you will,’ I told him soothingly, ‘and you certainly will. This can of beans, this little tin of mustard –‘

‘You have Colman’s mustard? Please don’t give me a heart attack of joy! With saffron rice or just a little sprinkle in the chicken soup! - ’

‘As I was saying, this can of beans, this little tin of Colman’s mustard and even whatever is left of this sherry we are about to share – all of these things will be yours if tomorrow you will ask your son Hamza to drive us both to the Aden Sheraton. Yes, all these things and perhaps a little something special for Fatima from my make-up bag will be yours the minute you deliver me safely to that hotel. I give you my word as an Englishwoman and as a Flashman. Understood?’

‘Yes, perfectly understood,’ he said, humbly watching me take a first swig of the cooking sherry. ‘It will be an honour and my sacred duty to escort you wherever you need to go tomorrow.’

‘Until the moment that we arrive at the Sheraton all these things you love more than life itself will be returned to the suitcase which will be kept locked.’

‘Everything is clear, my dear – just one thing, you wouldn’t happen to have any Liquorice Allsorts, would you?’

‘No, I would not! What a disgusting idea!’

‘Haram! Shame! They carry the perfume of Paradise… or a tin of Golden Syrup, by any chance, which is so tasty with banana?’

‘No!’

Naturally, we polished off every drop of that sherry; I slept, still fully dressed, on one of the mattresses with my head resting on my suitcase for safekeeping.

Chapter Seven

A Foreign Affair

A Foreign Affair